T H E G O D S Z O N E

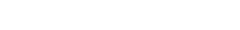

The Smiths

Muir Trail Ranch

Dear Dad,

Thank you for the mountains. You gave

us the most incredible gift. Rivers and trees and rocks, forty horses in our backyard and as much space as we could possibly run in, all wild and beautiful.

And you gave us challenges, a chance to

learn the wonderful skills of the mountains and feel at home there……

Cam Smith

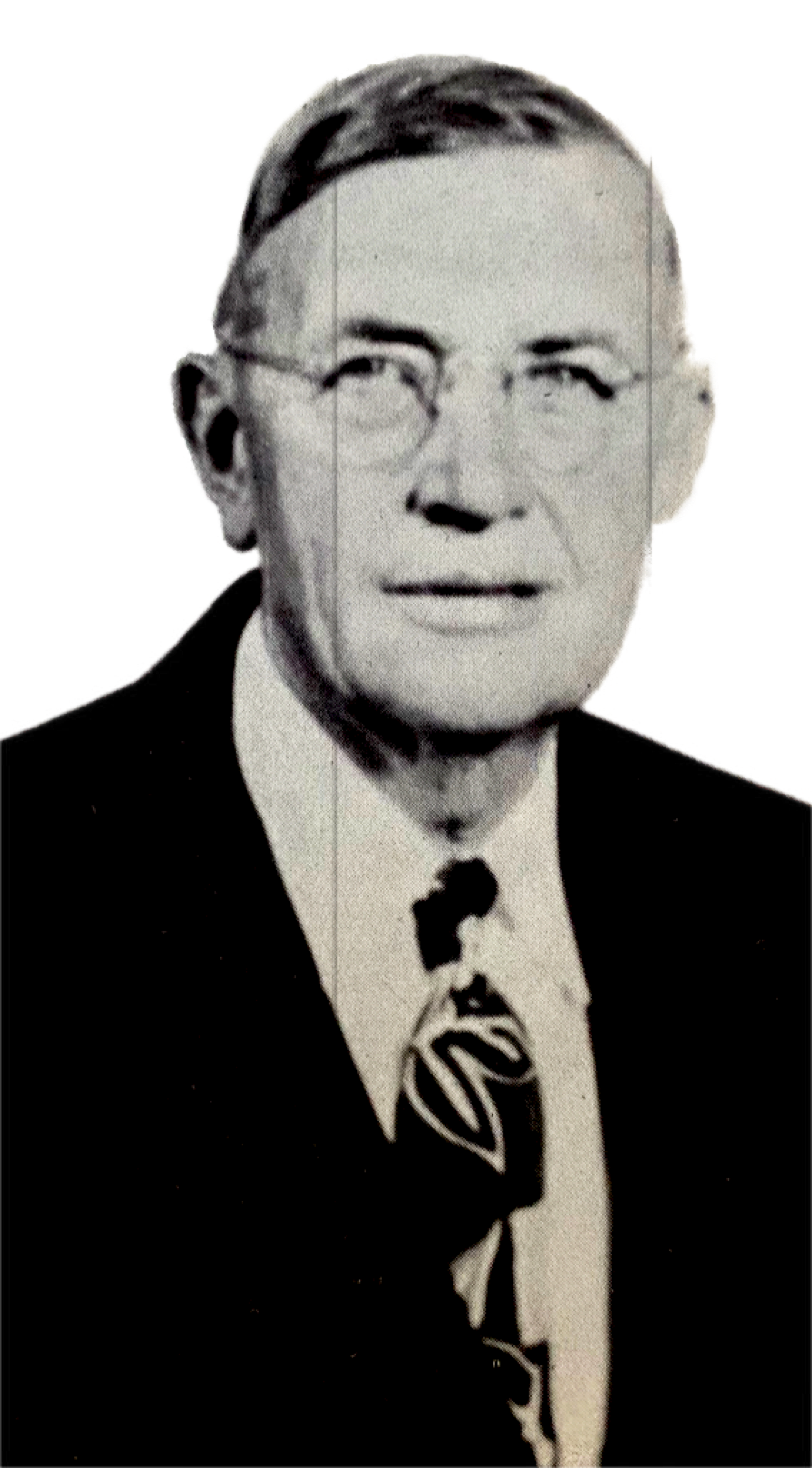

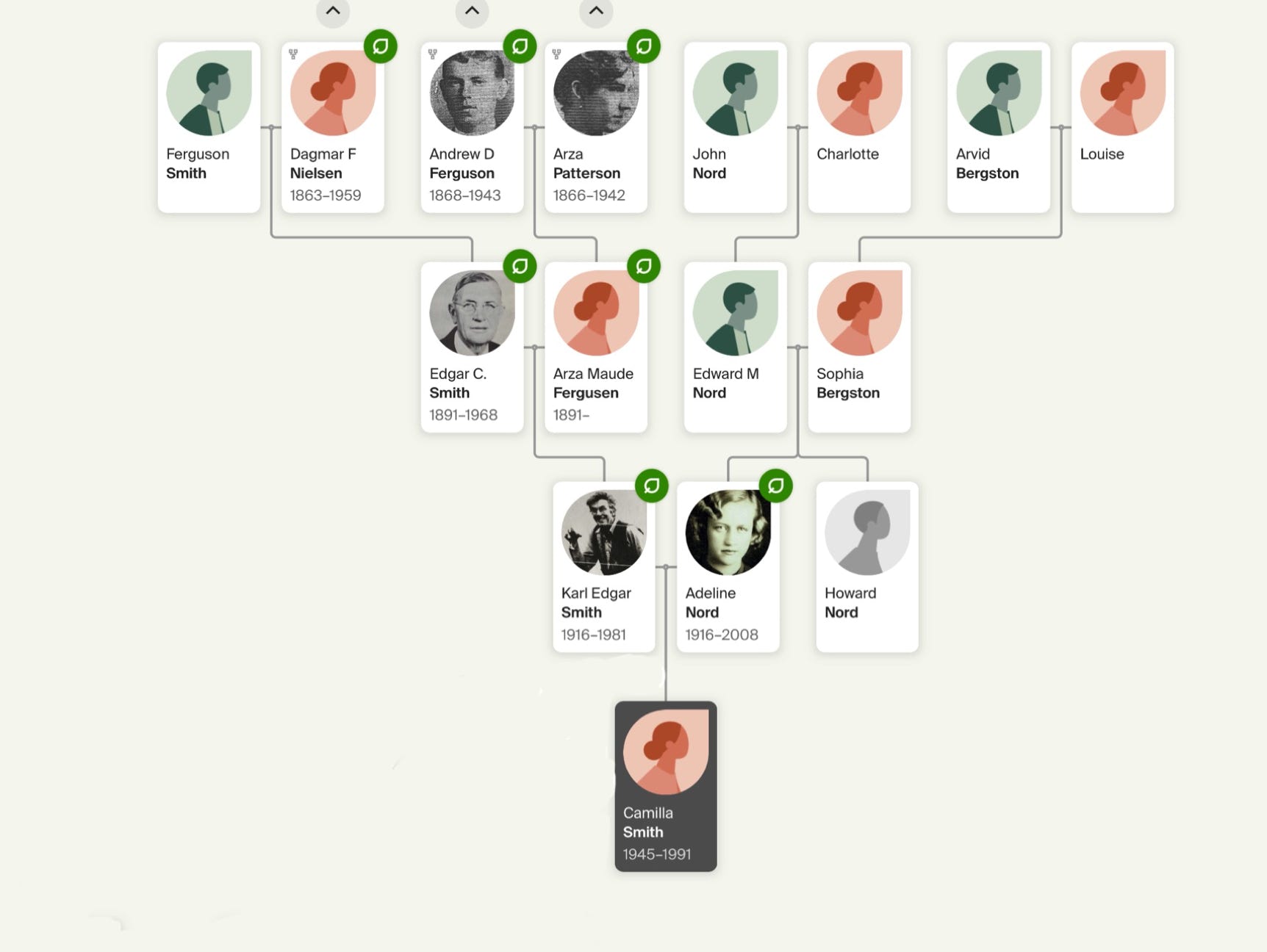

Karl Smith

Adeline Nord Smith

Karla Smith

Hilary Hutley

.

In the mid 1930’s as Lena Shavers health was failing, my father Charles Burr Craycroft (then in medical school at Stanford) arranged for Adeline Nord to be her companion for several years in the Mountains.

Later Adeline married Karl Smith and together they created the store and ferry at Florence Lake and Muir Trail Ranch. Through many trips to the ranch and the high country beyond over a period of 40 years, I got to know Adeline very well. From her stories, just the way she spoke about Lena, Lena came alive for me.

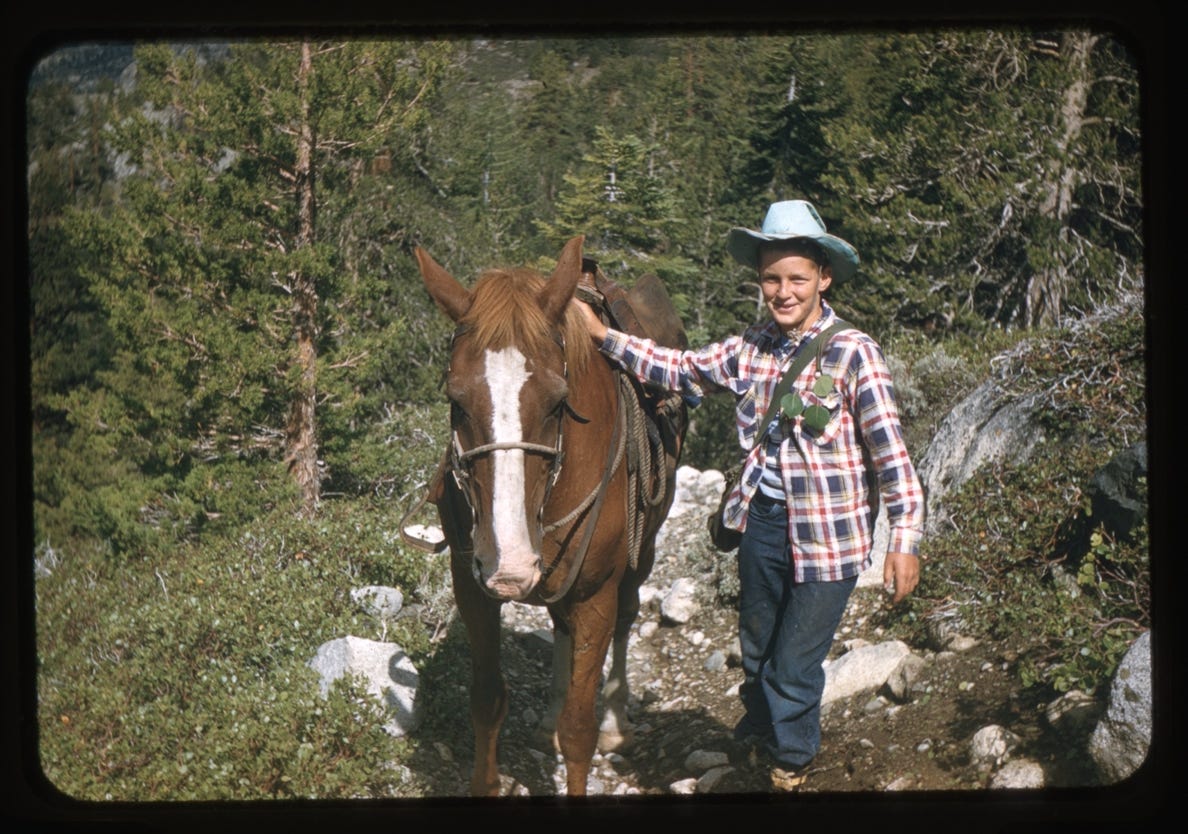

Adeline and Karl’s oldest daughter Cam was my age and we spent a lot of time together. Cam was a fusion of her mothers calm, confidence and strength and her fathers brilliance, generous and daring spirit. Karl died suddenly of a heart attack in 1981. Though Cam had become somewhat distanced from her family, in 1982 she wrote a brilliant, soulful letter to her father that expresses the heart and meaning of their place in the mountains and the meanings that they represented to so many and that captured me and set my path forever.

April 18, 1982

Dear Dad,

Thank you for the mountains. You gave us the most incredible gift. Rivers and trees and rocks, forty horses in our backyard and as much space as we could

possibly run in, all so wild and beautiful.

And you gave us challenges, a chance to learn the wonderful skills of the mountains to feel at home there.

And you gave us a philosophy, a philosophy we always thought of as the "mountain way" and one which I have recently thought of in looking at the roots of this country as an "American way", a "pioneer way”. In truth it is the way of mankind at his best, meeting all challenges, never giving up (never even

considering giving up), doing what you set out to do (and "If you're going to do it

something really hard do it right") doing just for the heck of it, being honest, helping those who need it, respecting the land and all life.

We learned to carry a piece of wood to leave on top if we were ever riding on horseback over Muir Pass, 12,000 feet high, because some hungry cold backpacker up there might need it sometime. We learned to love creation, working hard as a team, and solving every "impossible" problem that came along.

To this day I can't even imagine something like coming home without the horses, just because we couldn't find them. If some thing broke it was fixed. If it couldn't

be fixed it was fixed anyway. The "mountain way" was,'always coming through”. What a heritage.

And then there was the lesson of being close to all of the elements without the screens of civilization. What does the earth really feel like, and the rain when it

rains on you for 6 hours in the saddle? It is more than just "roughing it".

It was somehow very important to learning about being alive to know what a planet really feels like and sounds like and looks like when it's just you and the planet.

I wonder now how many of those wonderful "missions" you sent me on, like riding all night to bring back a saddle left at Rose Lake were absolutely as vital as they sounded at the time, but I know what it does for a kid to let them have such a great job.

I know what you have done for me, and I’ve seen what you have done for others, and I’ve seen the delight you always got out of sharing the mountains and all that went with them.

Many thanks, and I thought you’d like to know that your gift has not stopped here but will be passed on and on.

Love,

Camilla

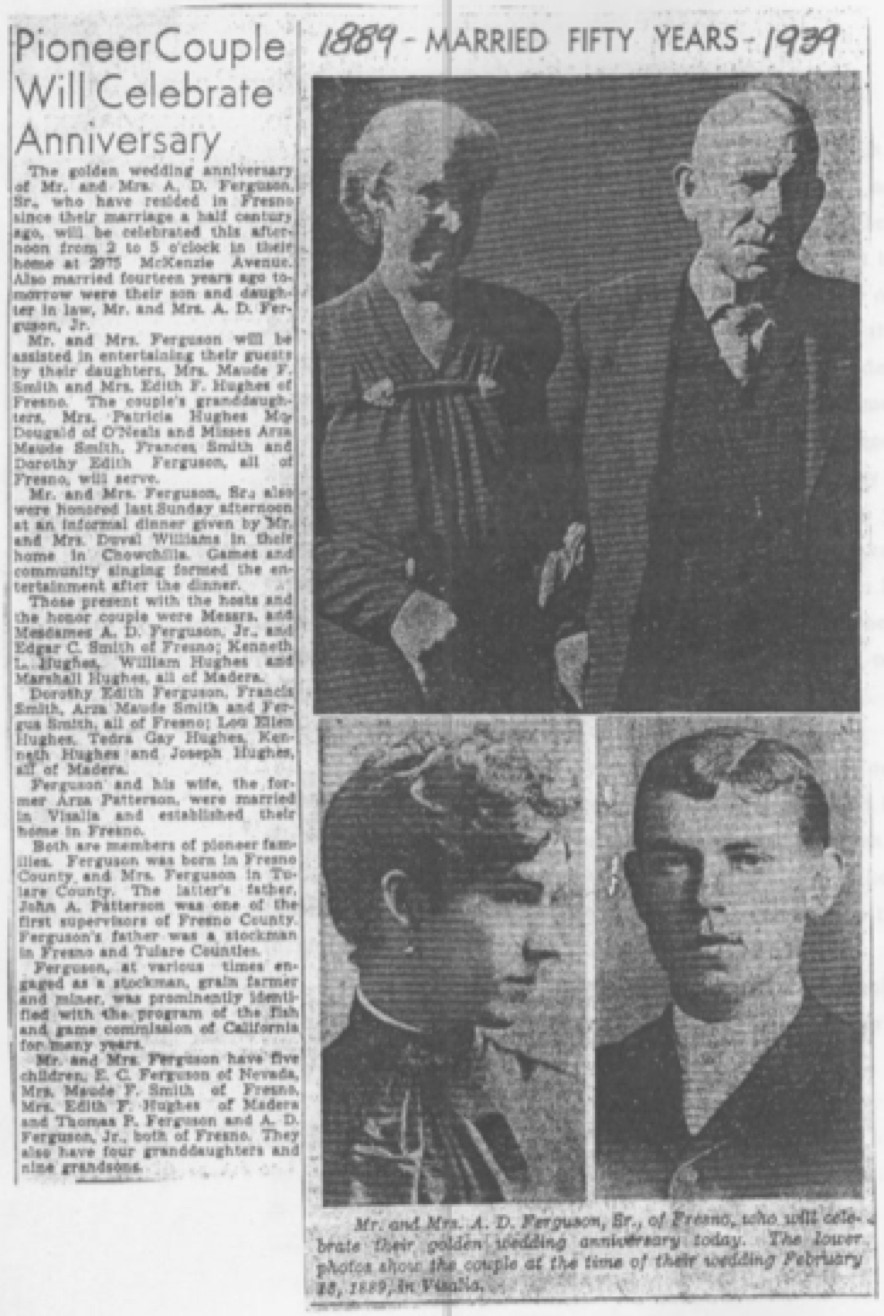

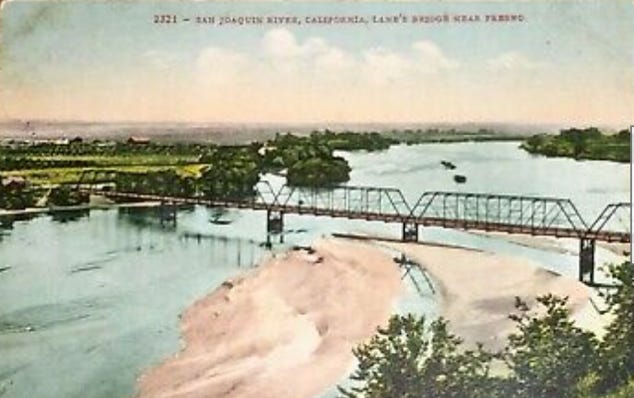

Andrew Darwin Ferguson was born in 1821,

Kings River, Fresno, California

When it comes to understanding the Mountain Way that Karl and Adeline passed on to Cam, Karla and Hillary, that inspires so many of those who have been touched by their lives and is epidemic in The Gods Zone, a very good place to start is Andrew Darwin Ferguson, Karl’s Grandfather. Andy was at various times a stockman, grain farmer and miner and is primarily identified with the role he played as Fishing and Game Commissioner of California, a role very dear to the heart of all who fish in the high country and certainly every member of The Shaver Lake Fishing Club. In his own words:

THE HIGH COUNTRY and Related Thing

Random Thoughts of a Mountaineer

Andrew Darwin Ferguson

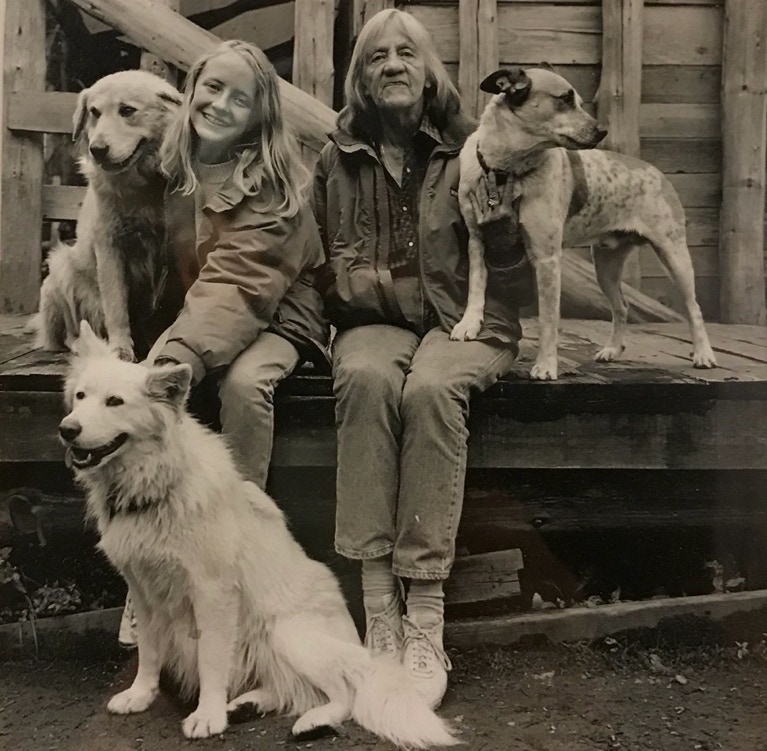

PUTTING TROUT OUT ON HORSEBACK

The conservation of wild life having become a live issue in California, the Legislature in the early 1890”s or late 80’s, incorporate in the County Government Act a provision for the office of County Game Warden. The various Boards of Supervisors of their Counties promptly acted and appointed Wardens. Most of the boards, I fear, were actuated chiefly by the opportunity for one more piece of patronage rather than from enthusiasm for conservation.

In 1896, I was offered the post of Game Warden by the Supervisors of Fresno County. In a flash it came to me that here was my chance to do something toward getting trout into our barren waters, and I accepted the post.

The office of Game Warden had been simply a sinecure and I think the Supervisors were greatly surprised to find that the new Warden

took the job seriously.

In '97 I gathered together a pack train and set about planting trout. And for four years, each Summer found me hard at it. The law allowed but twenty-five dollars per month for expenses, which was about the cost of getting a single consignment of trout fry from the railroad to the terminus of the wagon road where the heavy work began. I had, at various times, sixteen head of my own horses and four of my ranch employees engaged in furthering the enterprise.

Let it be understood, I was not a rich man indulging a hobby; I did, nevertheless, follow my hobby. To "make two blades of grass grow where one grew before" is proverbially commendable. It did not occur to me that to make countless millions of fish to grow where none grew before is an improvement on the grass idea. I was preparing to share my joys with my fellow man.

My first fish planting efforts involved taking the "fry" from the nearest railroad point, delivered to me by the California Fish Commission. Thence by stage an all night trip, to the terminus of the road where my pack train awaited me. There could be no stops or delays. Fifteen minutes in the cans without aeration is fatal to trout in course of transportation. Likewise high temperatures or a sudden rise in temperature of the water, be it SO little as three of four degrees, will cause the fish to sicken and unless the condition is quickly remedied the fish will die. While in the valley, temperature in the cans is regulated by the use of ice. In the high mountains. I had my cans covered with burlap which we kept saturated with water. Since mountain temperatures are not naturally high I found no difficulty in maintaining even temptratures in the cans.

And this soon led me to abandon the plan of using hatchery fish for transplanting. Instead we went into those places where hatchery fish were to be had and took adult fish for transplanting. Instead of 2500 to 4000 fry to the can, we could successfully carry but 50 to100 adults from four to six inches in length. Our adoption of the use of adult fish proved much the more

satisfactory. The adults spawned within a few months and the stream or lake

wherein they were placed was quickly and completely stocked. Eighteen miles between falls, of the waters of the south fork of the San Joaquin thus planted with a few adult trout was within three years of the plant a splendid trout

stream. The rule was invariable. Four years at most and a sizeable

river was trout waters par excellence.

To secure a supply of adult fish our first practice was to turn a small branch of the stream and, as the waters receded, the fish collected in pot holes where we took them up with nets. It was a laborious process.

Later and ever after we took our stock fish entirely with (fly) hook and line.

Taken on fly hooks the fish will not be injured if removed from the hook with a wet hand. We once took five thousand Golden trout from Volcano Creek with fly

hooks and transplanted them without losses -- a lesson for those who argue that it is useless to return immature trout to the water because "they will die anyhow."

Those first years of fish planting were the hardest, for it was necessary in securing stock fish, to go down into those deep canyons heretofore described and to bring the heavily laden mules out whole, this called for the exercise of much skill and labor.

Then, too, there were other hazards. In a precipitous country it is necessary to plant fish near headwaters and allowing them and their progeny to gradually scatter themselves down stream. To reach such headwaters, trails must be

abandoned and extremely rough going must be overcome. Without going into details (my descriptive powers are hardly in my equal to the task), I will cite one instance still in my vivid memory.

With a single companion to help handle a long string of pack animals, I was attempting to reach the headwaters of the north fork of the Kings, right at the foot of Mt. Goddard. We were coming from the south. About half way down, the mountainside soil gave way to a series of more or less connected benches on the side of a granite wall. Gradually we worked our way down to the last bench above the river. There it lay at our very feet. stream for our tired fish, grass for the horses, rest and supper for ourselves but, alas, hundred feet of smooth granite, steeper than the roof of a house, was between us and goal. To go back was impossible. We had brought stock our down over ground which no laden animal could climb back over. Dark was fast approaching and the prospect was anything but pleasing.

After fruitless attempts at finding a safe passage, I resolved to try a desperate expedient. My mount was my favorite horse, Conejo, intelligent, biddable, and possessed of absolute confidence in his master. We had been in many tight scrapes together, Conejo and I, and now it was a case of do or die. I led the noble animal right to the very edge of the bluff and parallel to the face. Then suddenly I pulled his head toward me in such a manner as to throw his front directly down the slope. There being no footing, he sat back on his haunches and began to slide. To guide him straight down, I held him by the chin strap of his bridle and slid with him. It was a perfect slide and we reached the meadow without the slightest mishap.

And now for the pack train. Scrambling back up to where Ken awaited me, we set about the toboggan business for the mules. Taking them one by one, we led the mules to the brink as I had done Conejo. To line them down the slide, as I pulled a mule's forequarters toward me, Ken, using the mule's tail for a fulcrum, swung his hindquarters in the opposite direction. Thereafter, there was nothing the mule could do but slide -- and I slide with him. Thus we took the entire string into camp without spilling so much as one drop of water.

I would not willfully create the impression that my four years of pioneer effort at pack horse fish distribution was accomplished without help. The stock men of various sections of the mountains lent invaluable assistance, they

In addition to their personal assistance they furnished me horses whilst my exhausted ones were turned out to rest and recuperate. Their reward, like my own, was but the satisfaction of a good deed well done.In four Summers I was able to stock all the major waters of the two big watersheds, together with

the minor streams up to ten or eleven thousand feet elevation. These streams

satisfied the desires of the outing public for a long time.

In those years of experience I learned much of those details which make for success in fish planting. At first I attempted to "go easy" when carrying the fish.

I soon learned that time is the only element which makes for success.

If a journey at a leisurely pace required twelve hours, and if by hastening or even occasionally trotting the mules I made the same trip in six hours, the fish

arrived in much better condition. Rainbow trout will hold themselves clear of the sides of the can for about eight hours. Thereafter they tire and are injured or killed by coming violently in contact with their prison walls.

Lock Levin trout will carry safely one to two hours longer than Rainbows. While Golden trout can stand but six hours of this kind of transportation without twelve to eighteen hours rest. This knowledge was the

chief factor in my success. To rest the fish I placed the cans in a

flowing (cold) stream, putting, or course, a screen across the mouth of the can.

My longest successful carry by this method was two weeks -certainly the record.

Galvanized iron cans are bad containers for carrying fish. My first pack cans were of that material. After a time we discovered that a certain can invariably disclosed dead fish. We soon called it the coffin. I took my troubles to a tinner. Promptly he pronounced my trouble: zinc poisoning. My tinner friend made me a set of cans of block tin and thereafter all went well.

Looking backward it is amusing to recall the dire predictions of many people as it concerned my undertaking. Some argued that had the waters been adapted to the existence of fish, they would have been there all the time.

Others accounted for the fishless condition of many lovely streams on the theory that the streams once the carried just certain streams now do, but floods carried them fish as away. Summed up, it was the general opinion that my efforts would prove futile. Unvarying success, however, soon converted the doubters.

How those transplanted multiplied! And how fast they multiplied!

In the new waters there was a myriad of insect life. My colonists lived on the fat of the waters. Trout taken from the parent stream where, because of the struggle for existence none had attained a length of above eight to ten inches, promptly grew into, three and four pounders. And this situation continued until the streams became overstocked. Now six, eight, and ten inch fish are

the prevalent type except in lakes where the big fellows can still be freely taken.

At the end of four years the political wheel of fortune having turned, a good Republican got my job and fish planting in the mountains came to an abrupt end. I gracefully, not to say gratefully, accepted the situation and set about improving my neglected personal affairs.

I, through my work, was finished along "pro bono publico" lines, but in 1909 the Fish Commission of California importuned me to accept the position of "Assistant in Charge" of a newly created District Office. I was given nine counties wherein I was to administer the Commission's affairs and soon, naturally, I was again deep in fish planting game. I surrounded myself with loyal deputies, fine, active fellows who lent their enthusiastic support to

my plans. The Commission lent its hearty support, and we commenced "doing things" in a large way. I had my mind set on the hundreds of lakes in the extreme high country and was determined that they should be stocked. Motor trucks having come into successful use, the former long stage trip from rail lines to road's ends was no longer an obstacle, which enabled us in addition to our more pretentious undertaking, to bring many varieties of hatchery fish.

into the mountains.

Eventually I organized my locally famous thirty mule fishplanting pack train.

Sam Ellis picked the "string" for me and Sam knew mules. Throughout several seasons we continued our work, until there were no more worlds (waters) to conquer.

One day the Commission's chief officer, Mr. John Pease Babcock, called me into the head office and asked me if I thought I could bring out for transportation to the Sisson hatchery, some Golden trout. I replied "As many as you wish."The Chief smiled and reminded me that the Federal Fish Commission had repeatedly failed to bring out so much as one live Golden trout. "But", added the Chief, “I believe you can do it. That conversation resulted in the

Nineteen Eleven Golden Trout Expedition. My splendid Chief gave me carte

blanche to do all my own way.

Pardon the digression, friend reader, while I tell you how that I know

the fame of our 1911 expedition went far abroad.

In 1919 there came to my camp in General Grant Park, a globe trotter, the type which trots upon his own trotters. By the way, the right method of really seeing things. He was asking for trail information. Sensing that here was an intelligent gentleman, I insisted that he stay for lunch. Mutual introductions naturally followed. Upon getting my name he said: "Andy Ferguson, Andy

Ferguson, are you the man who wrote the 1911 Golden trout report for the California Fish Commission? I read that report in Sweden,

translated into Swedish."

(Author's note: These lines were penned in the hope that they will fall under the eye of my former chief, who is now Chairman of the International Fisheries Commission.)

“The Golden trout was found, naturally, in but one spot on the globe

Volcano Creek, recently renamed Golden Trout Creek. Hence the interest of ichthyologists and the angling fraternity.”