R

THE

UDES

I am beginning this families story with some of my cousins reflections on his Shaver and Craycroft heritage. Pictured above in Eritrea where he served in the Peace Corp, John has continued to dedicate a good part of his time to Eritrea while raising two wonderful children, grandfathering and writing grants for educational institutions. He is a great human and, as you may have already seem, for his reflections are scattered throughout this site, articulate and insightful.

18th December 2013, by John Rude

My daughter Amy, a well-read feminist, insisted that I include my maternal ancestry in this account. This I can do with pride equal to my recounting of the male Rude lineage, because the families of my father and mother had an abundance of strong women.

And yet, the two families were so very different. Even the names—Rude and Craycroft— have the slightest hint of opposing polarity, like the "Upstairs Downstairs" or "Downton Abbey" sagas on television. How did these two families, one pioneer-plain, the other seemingly aristocratic, come to merge, and what (besides the inevitable children) were the consequences?

I choose to begin with the Craycroft-Shaver branch, in part because it includes figures of minor historical importance—yet also because these ancestors had a tendency to explode brilliantly like elaborate Fourth of July fireworks, then fade prematurely (and permanently) into the dark sky.

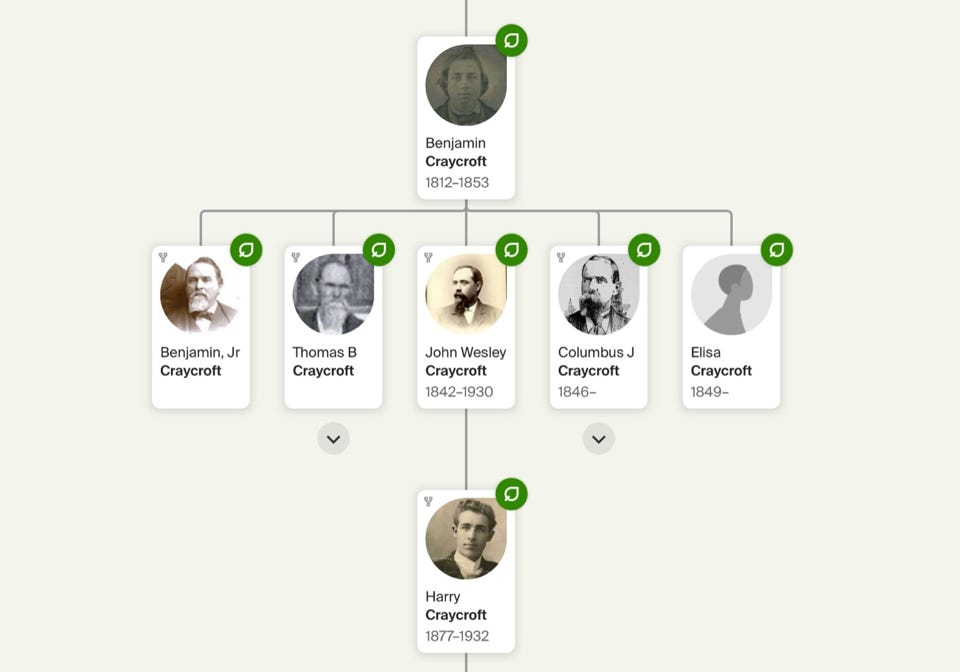

John Wesley Craycroft

His father, John Wesley Craycroft, was born in Missouri and died in Modesto, California at the ripe age of 88, just two years before his son Harry died in 1932. Photos of old John Wesley Craycroft show a distinguished 19th Century patriarch with a black three-piece suit, white beard and cane—an anachronistic throwback even in the late 1890s, when the pictures were taken. Harry’s grandfather was Benjamin Craycroft Jr., who died in Decatur, Illinois in 1853. His father, Benjamin, Sr. was born in Baltimore, Maryland, July 14, 1780.

Craycroft may sound like an aristocratic name, but its literal meaning is “crow farm,” indicating that our English Craycroft ancestors were yeomen, rather than gentry. I confirmed our humble origins during a visit to Westminster Abbey in London, where the chronicles of nobility contained not a single reference to the Craycrofts.

An extensive (and mostly fanciful) Craycroft history was written by John Henry Craycroft (my grandfather’s second cousin) in the 1940s. Another cousin, Robert Craycroft corrected much of this account in 2000. Both make for interesting reading.

Despite our obscure beginnings, the name Craycroft has long been on public display in two localities: Fresno, California and used for over a century throughout the San Joaquin Valley. In Tucson an arterial road named Craycroft stretches for miles across the eastern part of the city, spawning eponymous signs that advertise schools and businesses. The latter Craycroft is sure to be a relative, but the link is probably too tenuous to be significant.

A brief detour into another branch of the family is significant, however, because it may be our only known departure from the Anglo-Saxon tribe. John Wesley Craycroft was a college-educated itinerant evangelist and sheepherder. He married Alice Valpey, a woman of Italian descent. The story (passed on by her daughter Franke) links Alice Valpey to the House of Volpi of sunny Tuscany.

The link is said to go back to the 11th Century, however, (possibly to a Jersey knight returning from the Crusades)—so the story was probably intended to be a reminder that the Craycrofts and their next of kin have been very, very British for a long, long while. My cousin Peter Craycroft and I suspect that the darker features and wilder temperaments of some relatives might have more recent Mediterranean (or other) origins. Once again, additional research is needed—possibly DNA sampling.

See The Craycroft Family for more up to date understandings

Aunt Franke, dedicated archivist that she was, focused on her grandfather Captain CalvinValpey, who was born in Nova Scotia, apprenticed to the sea at age 12, rounded the Horn in his own schooner (The Eagle) in 1850 and a year later landed in San Francisco to seek gold in California. Valpey finally settled down to manage a general store in Warm Springs (Fremont), California. He left behind a place-name visible to all who travel by the Diablo coast range near San Jose—Valpey Ridge, a popular spot for hikers and campers.

The most illustrious place name in all branches of the family, however, must be Shaver Lake, named for my maternal great grandfather Charles Burr Shaver. Called C. B. (or “Cannonball”) by his many admirers,

Shaver was born in Steuben County, New York August 7, 1855. His family, of modest means, moved to a small town near Detroit, Michigan. There, after a bit of schooling, he started working in a lumber mill, where he was quickly promoted to foreman. Shaver moved from laborer to the business side of lumber in 1889 when he became general manager of White and Friant Lumber Co., Grand Rapids, Michigan. He distinguished himself by running a mill that cut 100 million board feet in a two-year period. In 1891 C.B. and his friend Lewis Swift toured the forests of California, and fell in love with what they saw.

On the steep slopes of Tollhouse cliff near Fresno, C.B. and Lewis Swift had an epiphany. The only thing that separated millions of dollars of timber in the mountains from eager lumber buyers in Clovis was the lack of an efficient means to transport the timber. Shaver and his partner visualized a flume, a man-made river suspended in the air, with planks shaped in a V, mounted over a roller-coaster-like framework of timbers. With the clear creeks of the Sierras providing the water to float the timber, there would be nothing to keep the rough-sawn planks from shooting down the incline, from virgin forests to insatiable markets.

C.B. and his partners began construction of his ambitious flume in 1891. By 1894, with an investment of $30,000 (and another $170,000 borrowed from others), he was floating thousands of kiln-dried planks 41 miles from his Pine Ridge mill to Clovis. “Cannonball”was well on his way to earning his first million dollars. As business manager, C. B. Shaver had to deal with the effects of a depression in 1893 that almost bankrupted the company. Robbers frequently held up the stage lines that carried payrolls up to the sawmill workers. Shaver faced the problem by issuing script payrolls to the workers, and dodging creditors in Fresno. The company was plagued withlawsuits, accusing Shaver of trying to sell flume water for irrigation that legally belonged to others. In Vintage Fresno historian Edwin Eaton (a distant relative of Shaver) describes the operation of the flume:

The customary procedure was to load the lumber into the flume at Shaver at night, sothat it would begin arriving at the Clovis planing mill and box factory at about six in the morning. At intervals along the flume were cabins of the “flume herders” whose duty it was to keep the flow of lumber orderly and to straighten out the jams that sometimes occurred... Because of its slightly steeper pitch and the sheer drop to the canyon beneath, the [Tollhouse] portion was one of the most thrilling and dangerous places for

company officials who occasionally rode a “flume boat” for quick passage from Shaver to Clovis.

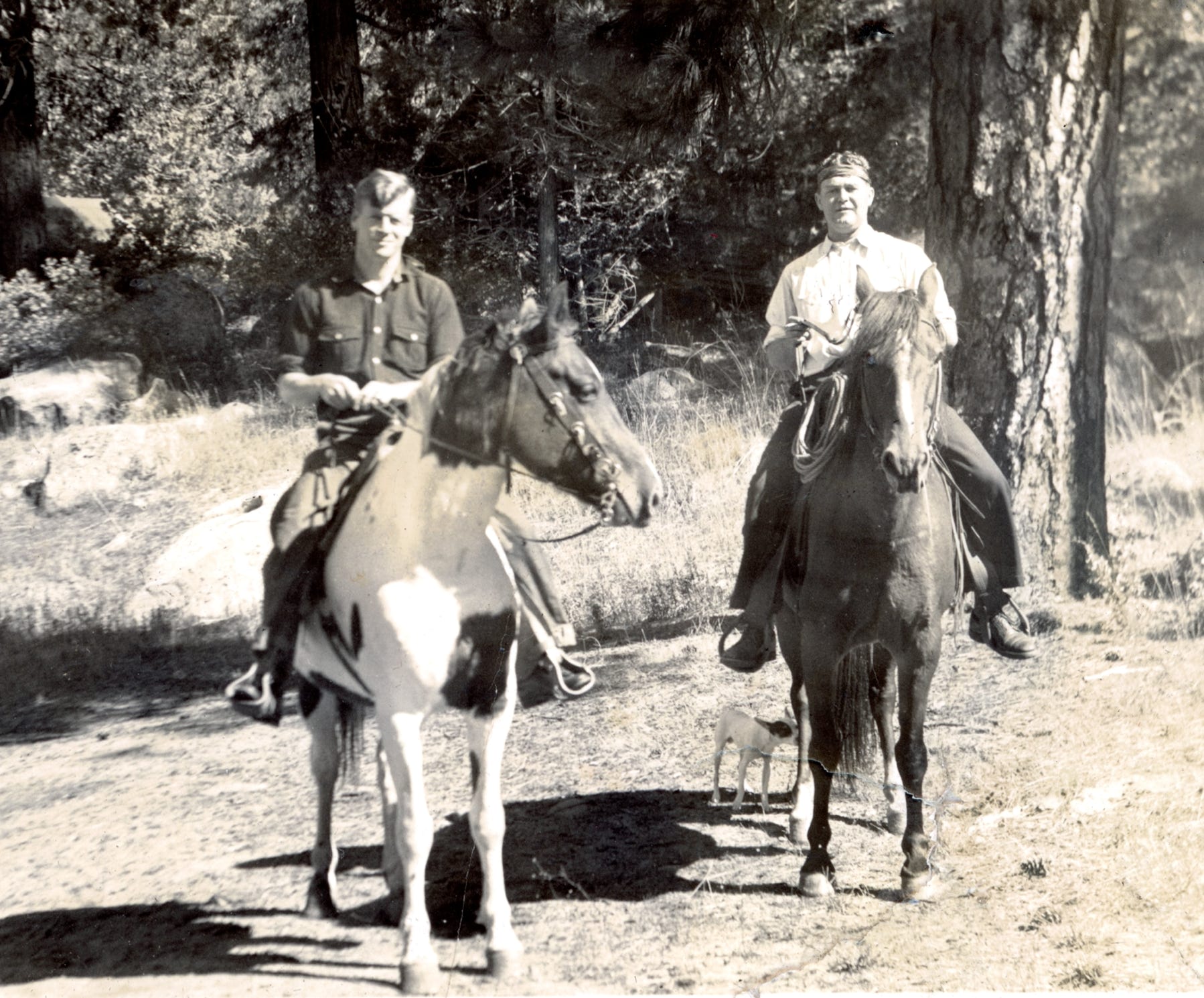

A contemporary description in the Fresno Bee depicted Shaver as “portly of figure, genial of countenance and passionately fond of a good cigar.” As he became one of Fresno’s most prosperous citizens, my great grandfather relished his status as a local celebrity. Citizens cheerfully jumped aside as “Cannonball” Shaver, with stogie planted in his mouth, raced the city’s first Stanley Steamer through the streets of Fresno. Dozens of photographs show him at the center of the action, sledding down Tollhouse on a cart poised atop the flume, riding horses, or posturing with his loyal friends and employees beside the massive sugar pines destined for his mills and flume. Yet Shaver’s life was not free of complications. In 1901 his partner Lewis Swift died suddenly of a heart attack. C.B. persuaded Lewis’ brother Harvey (whose wife happened to be the sister of C.B.’s wife Lena) to come from Michigan and take over the mill, so Shaver could concentrate on the operation of the Fresno Flume and Irrigation Company.

Shaver bought 2,300 acres of timberland, dammed streams and created millponds to ensure a plentiful supply of logs and water. Over the 20 years of its operation, the flume transported 450 million board feet of lumber. Nine million board feet were used to build the flume itself, a section at a time, over three years.

At the height of his affluence and influence, on Christmas Day, 1907 C.B. Shaver died in his Stanislaus Street mansion from complications of goiter and diabetes. He was only 52. Shaver was undeniably a patriarch who enjoyed life to the hilt, and had little regard— except as a source of wealth—for the old-growth timber that his company’s 200 fellers and sawyers and steam-driven donkey engines brought crashing to earth. Perhaps it is unfair to judge “Cannonball” Shaver by our current perspective, as today we are left with a legacy of only 5% of the Sierra’s original timber. One thing is certain: Shaver’s extravagant schemes and fortune might have evaporated into the mountain mist—like the tiny Mono Indian encampment at Pine Ridge that was neglected or worked to death by Shaver’s company—had it not been for the shrewd business acumen of Shaver’s widow Lena, the matriarch of the family. Seeing that the big trees were nearly gone and roads and trucks would soon make the flume impractical, Lena Shaver sold her share of the Pine Ridge mill in 1912. She also sold acres of clear cuts at higher elevations to Southern California Edison. The Edison company dammed Stevenson Creek in 1926 to create Shaver Lake as part of a string of hydroelectric power stations in the high Sierras. Using the $2 million she gained from these sales, Lena developed and subdivided an exclusive vacation enclave called Rock Haven (still a favorite getaway for Fresno’s elite). Next, she purchased the store, barn and hotel that had been built by Gus Beringhoff near the Pine Ridge sawmill.

Lena and her sister Minnie (Harvey Swift’s widow) deeply loved their 400-acre mountain paradise. Auntie Minn (as we came to know her, although she was long dead when we visited her mountain home) had a distinctive cabin built behind the hotel, graced with gorgeous Baroque revival cabinets and furniture. We loved to visit Auntie Minn’s Edwardian retreat, even when the knick-knacks were falling apart and covered with dust.

After C.B. died in 1907, Lena sold the Fresno Shaver mansion and bought herself and each of her three daughters—Grace, Ethel and Doris—comfortable houses on “L” Street in Fresno. Lena’s health declined in the 1930s, so she leased the mountain hotel to the Armstrong family for several years to keep her fortune intact. Heartbroken to be confined to the flatlands, Lena died on May 10, 1939 in Fresno, away from Pine Ridge, her heart’s home in the mountains.

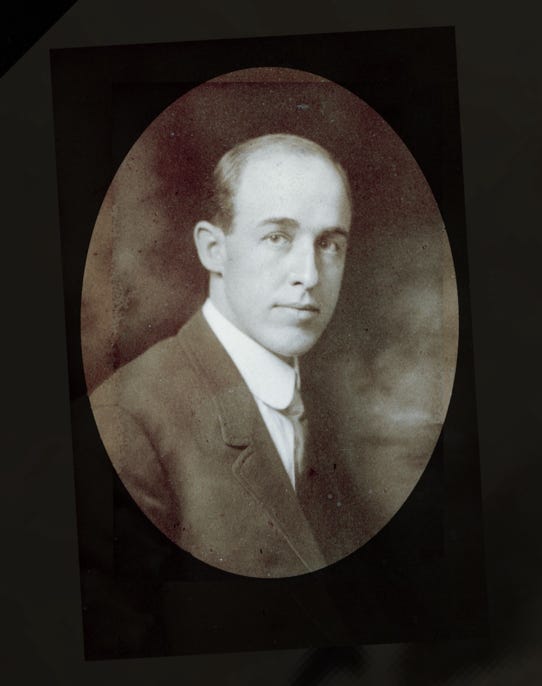

Lena’s daughter Grace (my maternal grandmother) was born in Blanchard, Michigan in 1887, but grew up in Fresno. Grace Mabel Shaver married Harry Judge Craycroft on October 6, 1909. Harry was a physician employed by Grace’s father to treat injuries (primarily broken bones and amputations) in the hazardous Shaver sawmill operation.

After their wedding, the couple moved to Fresno—to “L” street, next-door to Lena. Harry thrived in surgical practice while Grace produced babies (Marian in August, 1912 and Charles Burr, known by his middle name, in 1914); she also maintained a busy social life.

Before Marian’s birth, the couple spent a year in London and Vienna, where Dr. Harry Craycroft studied advanced surgical techniques.

Seven years later (1917-18) U.S. Army Major Harry Craycroft applied his skills treating countless wounded soldiers in hospital tents near the front lines in France. By all accounts the 23-year marriage between Grace and Harry was happy. In 1923 the couple moved to Pine Street in Fresno. Photographs of Marian and Burr in those years, along with their

parents, provide convincing evidence that the Craycroft family enjoyed material comforts and social prominence.

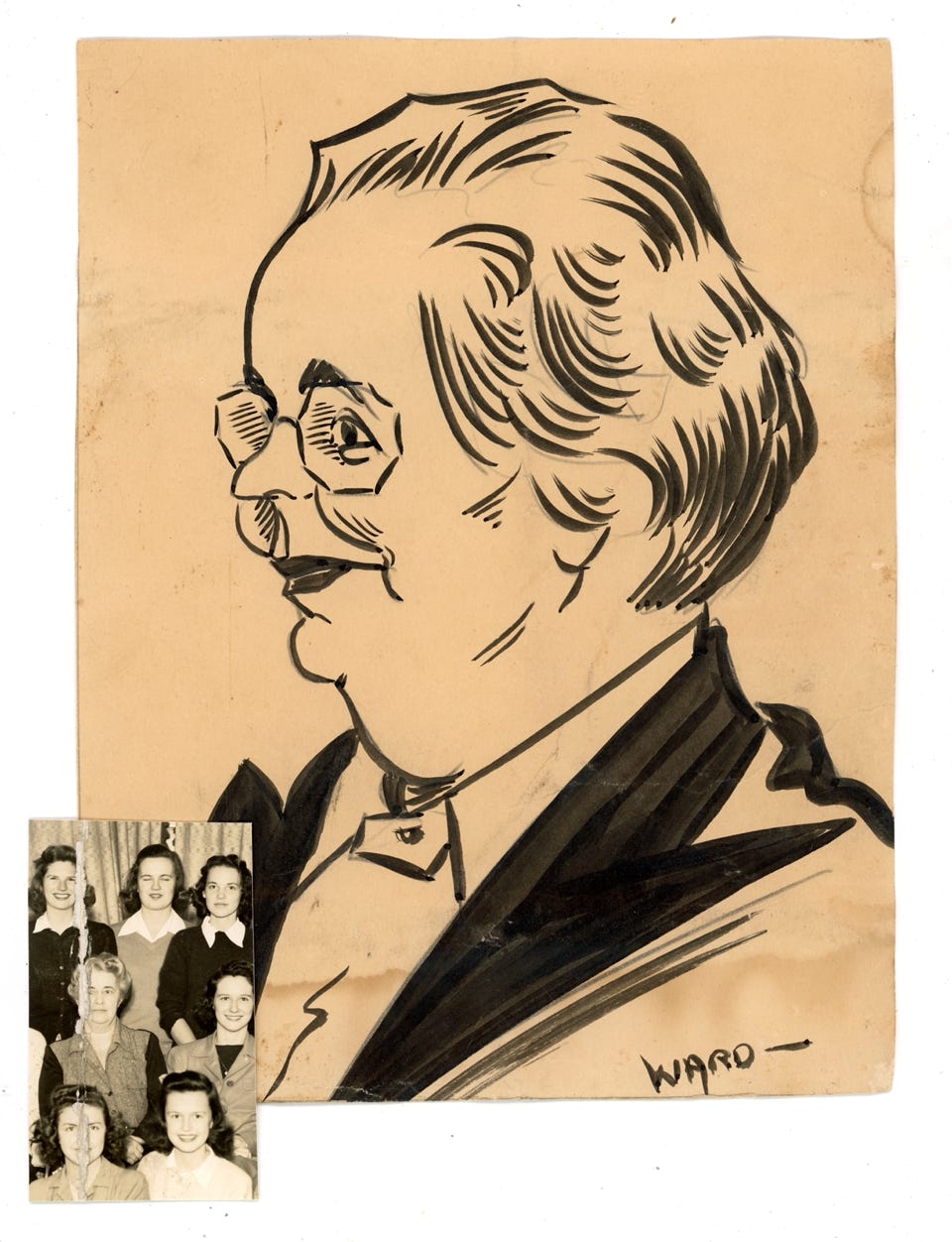

Despite the surface sheen of affluence, a few stories have passed through the filters of family pride to be picked up by the sensitive antennae of later generations. Harry earned a good deal of money as a doctor, and he had access to Grace’s fortune. He also loved to fish, bet on horses and play poker (a habit acquired during his saw-mill days). A cartoon in the Fresno Bee shows Harry as one of the champion “liars” of the Shaver Lake Fishing

Club. His companions loved to hear his stories. One, Emil Gundelfinger, told me years ago that Harry’s friends made sure a bottle was always at his elbow.

Whether Harry became alcoholic—or was just a lovable guy who drank a bit—may be impossible to sort out at this distance. If alcohol didn’t kill Harry (he died of pneumonia at age 55 in 1932), the addiction certainly became his daughter Marian’s nemesis, and was a factor in the relatively youthful death of his granddaughter Carolyn Craycroft Thomas at

age 61 in 2003.

Given our current understanding of genetics, it seems proper and wise to issue a warning to all who carry the Craycroft DNA: there is a chance that you carry an inherited tendency toward alcoholism. Like one of Harry’s numerous bets, it is a risk not worth the suffering that would surely follow you if you carry the gene. Sometimes tragedies arrive in pairs, separated by a single generation. Grace lost her father soon after her 20th birthday; coincidentally, Marian’s father died just as she had reached the same impressionable age. The psychological impact of these deaths may

have been profound, or they may have been slight, but one thing is certain: both women lived their adult lives depending on their widowed mothers for support and affection.

As a relatively young widow of 45, Grace began a new and satisfying career as a “house mother” for college sororities. Soon after her son and daughter had married and left Fresno, Grace moved to Berkeley to “mother” Pi Phi sisters, then moved on to UCLA (Alpha Phi) and Stanford (Kappa Kappa Gamma).

With her intellect, warmth and social ease, Grace was a comforting mentor for hundreds of California’s privileged women during the Depression years. She loved her charges deeply, but her most unwavering loyalty was given to her daughter Marian, to whom she wrote letters weekly over the next decade.

My mother was a natural beauty. Her friends, in the fashion-conscious Twenties, were forced to put in greater effort to look like silent movie star Clara Bow, or to behave like a moody Fitzgerald character. I’ve puzzled whether my mother was self-conscious about her beauty, but I’ve never doubted that she had it—or IT, as this mysterious quality was

known in the Jazz age. Neither did Max Hayden have any doubts. Max was one of Marian’s more articulate boyfriends (eventually becoming her fiancée).

She has dark, bobbed hair that I feel like mussing when I get the chance, but haven’t done so...yet. She might think it fresh of me. Her face is the setting for a most disconcerting pair of blue eyes. They are so expressive

in one way, yet always seem to keep a secret—something that sometime

might be said, but never really understood.

From her mouth come the most amusing thoughts. One longs to stop

them with a kiss. The The curve of her cheek, the color of her hair simply

cannot be forgotten. In other letters, Max lapsed into pseudo-poetry, followed by reasonably good verse to plumb the depth of his feelings for my mother. Some samples:

And I thought I liked her in blue, but she’s adorable in pink, but what I

liked best was the way she called on me when she had the blues. She

said nobody loved her, silly girl.

What could make her blue? She had a date with me recently—no, that

couldn’t be it. Maybe I did something. If I did, I’d be sorry, but I would

secretly be a little glad that I could make her blue.

* * *

There passed before me a vision —

all in blue

with trailing scent.

Pretty hands in graceful gesture

dainty hands in measured rhythm

For some small reason she laughed

the sweetest little laugh

Flicked back her hair with graceful shake

and started upon her way.

Other boyfriends clearly lacked Max’s debonair charms, but she saw fit to preserve their bumbling attempts at wooing her. First a boy named Dick, followed by George:

Dick: I am very ashamed of the way I acted last night. I wouldn’t have

embarrassed you for anything. I have enjoyed very much having a

sensible girl for company, not because of any personal favors that you

could give me.

George: What I said about you will never be known, I’m afraid. Alas and a

woe. But really, Marian, it was said in a complimentary way, and it was

very true for you, don’t you know? (Signed)

Your timid knife-wielder.

Marian’s brother Burr, only two years her junior, was a faithful letter-writer. His letters are mostly limited to the comings and goings of family friends. However, a few snippets from his letters from Stanford suggest that he was paying attention to Marian’s social standing:

How are your studies coming along? I hear you’re the apple-polisher

supreme...The annual Military Ball is coming off here and I’d like to have you go with me. If you do, I can get you some dances with an All-American or thepresident of some-thing-or-other....Thanks a lot for the date; I surely had a good time. I think you’re the best sister a fellow could have... Well, I went to “The Drunkard” again and thought of you all the time, especially when they sang the songs at the end. At the Alpha Phi “jollyup” the other night everyone seemed to want to know what you were doing....

The Dekes are having a tremendous drunken brawl across the street, and

I can hardly hear anything...

There is little to suggest that Marian’s ambitious social whirl was meant to achieve any specific goal. It is more likely that she lived largely according to expectations, as the scion of a prominent family. Her beauty could have raised the stakes somewhat: it is not unusual for women with attractive appearances and money to fall into a miasma of vanity.

But my memory of my mother is of a mature woman who was camera-shy, and far more ready to laugh at herself than others. To be sure, she hadn’t, as a young girl, acquired the doubts or physical and psychic wounds that became so evident in her later years. It’s possible that she flirted with the power of her image, and indulged in a bit of manipulation. But I have the clear impression that her friends—and eventually my father—admired her

for her authenticity, rather than for her artifice. Another psychological trait makes an appearance in one of the letters that her mother’s friend, Vivian Curtain, sent to Grace.

Well, your daughter got away yesterday on the Santa Fe Streamliner. You

probably know by now whether or not she went on from L.A. In spite of

the disappointments, excitement and nervous tension, I think she was not

too tired to relax when she boarded the train, and she knew that she was

really going. And she kept her head through it all and planned everything

out in a remarkably cool manner. I would have been too jittery to speak

under the same strain. She looked adorable in her new suit, and there is

some comfort in knowing one looks well.

It requires only a little between-the-lines reading to see that Marian had a streak of anxiety that ran through many aspects of her life. I can remember the “jittery” feeling that she emanated on many other occasions, which she concealed on the Santa Fe train. Whenever a thunderstorm passed, for example, she would draw Sally or me into the closet for the duration of the storm. She always made sure there was a light in there for reading or drawing. Most of the time, my mother’s anxiety was masked by a drink or cigarette, never far from her grasp. Alcohol eased her trip to L.A. to attend college. The last line of Vivian Curtain’s letter to Grace speaks volumes:

We had a hilarious time (for us) Monday night on just one highball, and wished you were with us.

My mother’s album of clippings reveals a reasonable, yet somewhat sinister, basis for her anxiety as she boarded the train for Los Angeles. One of her fondest ambitions had just been crushed.

Some background: Marian’s Fresno education was aimed not so much at a prestigious university education as a prestigious sorority. As early as age thirteen, she and her mother sponsored teas for Entre Nous, Fresno’s counterpart for the Cotillion Societies found in larger cities. Most of her album consisted of clippings of Entre Nous girls who gave their

own teas, and eventually were pledged to the best sororities at the University of California in Berkeley. There was no reason, academically or socially, that Marian would not follow the same well-worn channel—clear water from a pioneer stream flowing toward the larger ocean of sophisticates in the Bay Area.

But a 1930 article in the Fresno Bee reveals that her expectations were dashed in the cruelest possible way:

Anonymous letters written by some girl in Fresno to the six leading

sororities at the University of California urging them to deny admission to

Fresno girls have caused a furor among the parents of the girls and

started an investigation to determine the identity of the writer. Who was

the writer of the letters, which were meant to blast the hopes of the girls?

A handwriting expert, it is understood, has been put on the case by

several of the parents and if the identity of the scribbler is revealed by this investigation further action may be taken. The letters were sent to the

“Big Six” (Kappa Kappa Gamma, Pi Beta Phi, Delta Gamma, Alpha Phi

Theta and Alpha) and have caused no end of gossip throughout sorority

row. The letters were sent just before the rushing season and their evident

purpose was to keep Fresno girls out of these houses.

Details of this incident were never explained to me, other than my mother’s vague references to her disappointment at not pledging the Kappa house at Berkeley. We can only guess at the identity of the girl who wrote the notes, what she said, or who might have been affected by her poison pen. All we know as family history is that Marian attended Berkeley for one year, didn’t pledge any sorority, then transferred to UCLA in Los Angeles for her final two years of college.

Today I think of UCLA as a giant institution, which it most certainly is. But in 1931, when my mother transferred there, the university had only in the previous year moved its campus from Vermont Avenue in North Hollywood (today the site of Los Angeles Community College) to the 419-acre ravine in Westwood that it now dominates. There were only four buildings at the center of the campus. The “university” did not offer a Master’s Degree until 1933, or a Ph.D. until 1938, long after my mother had graduated.

My mother pledged Alpha Phi sorority and settled into life as a young member of a far more conformist, homogeneous Los Angeles than today’s metropolis. Nearby Westwood theaters were showing films such as Murders in the Rue Morgue with Bela Lugosi, or Pack Up Your Troubles with Stanley Laurel and Oliver Hardy. Gene Autrey was beginning

to popularize “honky tonk” music, and Duke Ellington was giving jazz a new face with “swing.” The Los Angeles Theater, built at a cost of $1 million in 1931, was the last major theater built on Broadway in downtown L.A. This French Baroque palace, with central staircase and gold brocade drapes opened with the premiere of Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights.

Marian arrived each semester by train at Central Station, which was replace in 1939 by Union Station, a still-functioning art-deco architectural jewel. Unless her friends picked her up in their motorcars, she had easy access from downtown to the west side by Red Cars—a sensible mode of electric transport that auto makers were then in the process of undermining, through buy-outs and bribes to make space for freeways. On many occasions Marian might have hired ataxi; there is little to suggest that the Craycrofts lost much of their fortune in the Wall Street Crash two years previously.

The Alpha Phi house on the UCLA campus was built shortly before Marian moved in, and still stands on Hildegard Avenue—“fraternity row.” Other fraternities and sororities pledged African-Americans students (Delta Sigma Theta) and Asian-Americans (Chi Alpha Delta). In light of this racial diversity in her own time it is surprising to read the following L.A.

Times description of an Alpha Phi “triumph”:

Alpha Phi places Second in Hi-Jinks with its artistic production, “The Sacrifice,” which portrayed a ceremonial rite of Africans dancing to the musical sounds of a monotonous tom-tom, the “black men” fiendishly gloating over their sacrifice of a beautiful white girl.

Some sorority high jinks were more benign, as another Times article attests:

Hildegard Avenue [sorority] houses have been the scenes of many holiday

parties, but members have not forgotten those less fortunate, and nearly

every house along the row has adopted one or more poor families in Los

Angeles. Where there were children in the family, these young Fairy Godmothers provided generously of toys and clothing.

Marian Craycroft is listed among the sorority sisters who were “particularly active” in such charitable activities. No record survives of her dramatic role (if any) in “The Sacrifice.”

In 1932 a shattering event hit my mother that was never recorded in Marian’s scrapbook or letters: her father, Dr. Harry Judge Craycroft, died of pneumonia. With such a glaring blank appearing in the otherwise detailed record of her life, I pleaded for more family stories from my cousins, Peter and John Craycroft. Their email responses put this sad event into perspective. First, Peter’s reply:

Harry was extremely generous. He was gregarious and liked to make bets

in the context of daily life. One example: he was always betting double or

nothing for a pair of new shoes with the storeowner, a long-time friend.

He seemed to enjoy losing as much as winning.

Harry studied surgery in Germany after the war. He had discovered in the

midst of combat casualties from both sides that the Germans were far

ahead in their surgical techniques. He taught what he had learned to

surgeons in the U.S. upon his return, free of charge.

Harry took great pride in his Pierce Arrow. Imagine Harry, with family in

tow, grinning at the wheel, flying up the intense grade to Shaver, overheated cars strewn in his wake.

Obedient to Lena (it was not easy!), he was deeply in love with Grace,

giving to his children (to a fault) but distracted by his clients needs and

still tormented by the war. Keep in mind that Harry and Burr need to be seen in the context of their outstanding contributions as Family General Practitioners. My father was one also. As children we were taught to always be prepared to defer to the larger family, our father’s patients. Being a GP was not a job; it was a calling. Doctors carried huge burdens. They worked very, very hard. Bone-crushingly hard.

I, for one, completely forgive Harry for what distracting pleasures he may

have taken.

A yellow newspaper clipping from 1919 or 1920, saved by Aunt Franke, was among John Craycroft’s collection of family memorabilia.

Major Harry J. Craycroft, tall, sinuous and sunburned, is back from overseas, full of interest in his experience of two years of service in Uncle Sam’s uniform. He generalizes his impressions with a hearty, “the Army treated me right.”

Dr. Craycroft was operating surgeon at Camp Fremont. He received several promotions that caused him to go overseas in October, 1918 with

the rank of captain. He was stationed at Periguem with base hospital unit

No. 95. His responsibilities increased with his appointment to chief of the

surgical staff and later to the commanding officer of the hospital,

whereupon he received a major’s commission. Five thousand patients

were treated at this hospital, including a number of German prisoners.

Major Craycroft spoke highly of the treatment given to American prisonerswho, after the Armistice, were transferred from German hospitals toPeriguem. Their surgical treatment had been fine, he said, but from lackof proper food they were all thin.

The lengthy article went on the describe the first Armistice Day exercises, as French and American survivors planted flags on graves in their respective cemeteries. Offered the chance to fly over the grim, silent battlefields by air, Harry turned down the offer down in order to tour through Brest and Chateau Thierry (how else?) by motorcar.

John Craycroft elaborated on how Harry purchased a car after the war.

Dad told me that Harry was driving in Fresno in his old Lincoln when the

engine started to miss and knock as it threw a rod. He pulled to the curb

and walked a few blocks to the Pierce Arrow dealer, bought a new touring

car and drove home.

Marian was in her junior year in college when her father died. I’m sure that she left UCLA and went to Fresno for his funeral, and grieved with the family at Pine Ridge during the summer before returning for her senior year. My cousins duly noted Harry’s intellectual curiosity, impulsiveness and gregarious nature. These can be traits that endear a person to strangers, but sometimes alienate family members who long for a more intimate relationship. I suspect that Harry’s “giving to a fault” to his children and his penchant for “distracting pleasures” might offer clues to a less sunny side to his temperament. In any case, Harry’s hard work came to an abrupt, premature end in 1934. Surviving members of his family moved on with their lives, leaving few mentions of him in their numerous letters, either before or after his death.

Harry Craycroft (a name with unintended irony, since his photos reveal that he was the precursor to my baldness) was my maternal grandfather. He died at age 55 of heart trouble, complicated by pneumonia.

We know know that Harry most likely died from a pulmonary embolism due to a genetic marker called Factor V Lieden which has more recently been shown to be present in the Craycroft and Rude families.

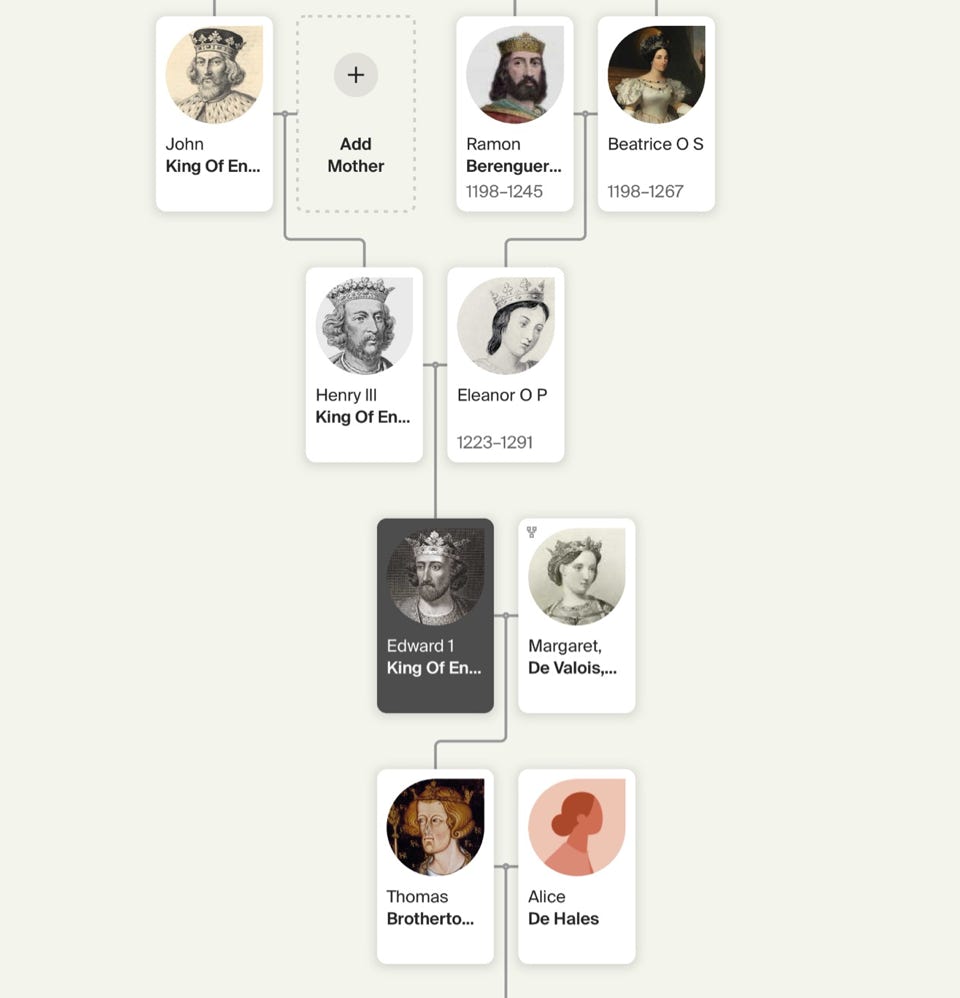

Five generations of Craycroft slave

masters and mistresses in Maryland 1558 - 1801

Actually, since John did his research in 2013, ancestry.com reveals that Harry’s ancestry does trace back to Edward !, Henry III, King John, Charlemagne and Hildegard. As the brilliant historian Jean Hemphill Craycroft cautioned, know the history of your family for it informs you of your meanings, attitudes and possibilities. Forget it and focus on your actions for it is alone by them that you will prove your worth and will, in